The Fairness Dilemma: How our sons develop Morality

Helping young men build a moral compass in a noisy world

"If a big guy is attacked and the smaller one fights back, nobody blinks when the bigger guy defends himself. But if it’s a woman who attacks the guy, and he defends himself, suddenly he’s the villain. How is that fair?"

This came from a late-night chat with my son. He wasn’t angry. He wasn’t ranting. He was thinking... trying to make sense of justice, morality and gender in a world that sometimes punishes him for simply asking the question.

Conversations like this aren’t rare, from online forums to dinner tables a growing number of young men are articulating the same discomfort - what could be called the fairness dilemma. It’s not emerging misogyny which some might first jump at as a conclusion. These young men believe deeply in respect and equality and they often come from egalitarian households but they can feel betrayed and hurt when trying to square their sense of morality – which is rooted in fairness, reciprocity and decency - with social narratives that sometimes seem stacked against them.

Understanding the Fairness Dilemma

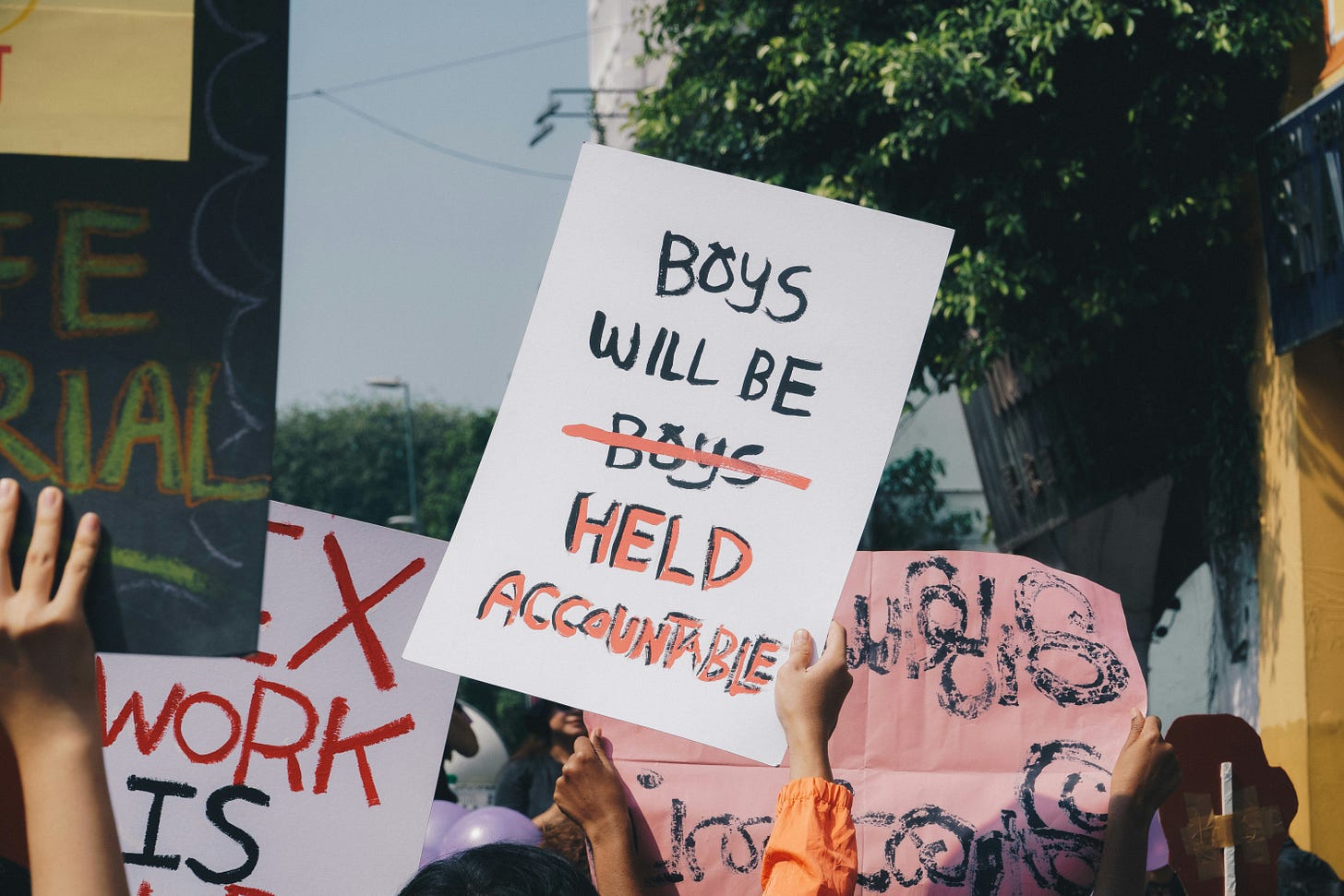

The fairness dilemma refers to a pattern in which young men interpret cultural or institutional messages not through a socio-cultural lens but through a procedural one. They aren’t evaluating fairness in terms of structural inequality for example - they’re looking for rules that apply to everyone equally. When boys are mocked for being vulnerable, when male victims of partner abuse are dismissed, when slogans like "all men are trash" go unchallenged - it feels like a betrayal of the values they’ve been raised with.

"Being told I’m just like all men is unfair. I’m not. My friends aren’t. We’d never hurt anyone."

Moral Development and Black-and-White Thinking

This framing of violence and fairness is a good example of how many young men at this stage are reasoning. His logic - centred on symmetry and justice - is in line with what Lawrence Kohlberg described as the conventional stage of moral development, where fairness is rooted in rules and reciprocal treatment. Paradoxically while my son acknowledges “context is everything,” his animated responses - like many young men’s - reveal how difficult it is to hold nuance when feeling misjudged or excluded.

Kohlberg’s Moral Reasoning and Gender

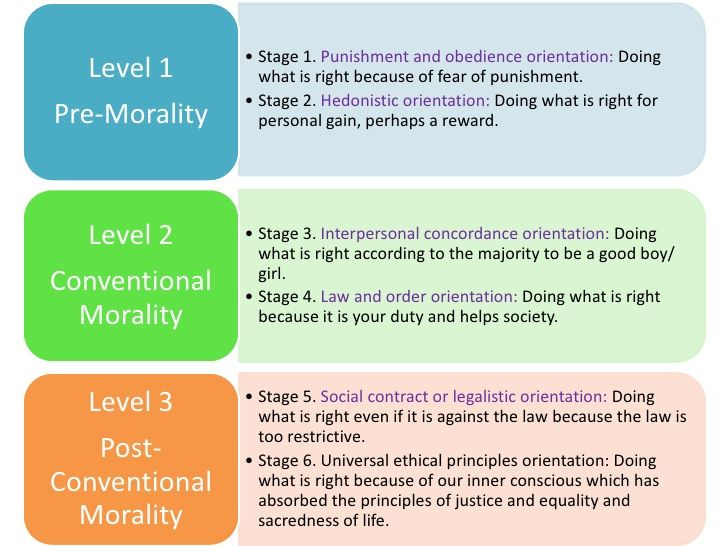

Developmental psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg proposed that moral reasoning develops in a series of six stages across three levels: pre-conventional, conventional and post-conventional.

In the pre-conventional level (Stages 1 and 2), morality is externally controlled:

Stage 1 – Children obey rules to avoid punishment

Stage 2 – Morality is driven by self-interest and personal gain

At the conventional level (Stages 3 and 4), morality is about conforming to social expectations:

Stage 3 – Behaving to gain approval or avoid disapproval (good-boy/good-girl orientation)

Stage 4 – Maintaining law and order; fairness is found in consistent rule application

The post-conventional level (Stages 5 and 6) involves abstract reasoning:

Stage 5 – Recognising laws as social contracts that can be changed for the greater good

Stage 6 – Adhering to universal ethical principles even when they conflict with existing laws

Most people don’t reach these higher stages. The dissonance many young men feel when expecting fairness as rule-based symmetry whilst facing contextual interpretations of justice often reflects that they are reasoning at Stage 3 or 4 while being asked to engage with Stage 5 or 6 morality. This disconnect can feel not just confusing but unfair.

Kohlberg’s theory helps explain this tendency as most young adults operate within Stages 3 (good-boy/good-girl) and 4 (Law & order where fairness is found in equal treatment under sacrosanct rules and laws).

Rule-Based Fairness vs Structural Justice

My son’s reasoning - “if it’s wrong for one, it’s wrong for both” - echoes a broader moral framework common among young adults, particularly young men. For many in this stage justice feels simple and rules should apply equally to everyone and when they don’t the system feels rigged.

This framework tends to view interpersonal morality (e.g. violence, truthfulness, loyalty) as straightforward: if one person is punished for hitting someone then anyone who hits should be punished regardless of gender, context or history.

When these two moral frameworks collide young men may feel vilified despite their good intentions or despite their goodness. They feel like they’re playing by the rules but are still losing and we as the ‘adults in the room’ should be careful how we react to those questions and conversations.

When Language Closes Doors

One of the recurring themes in conversations with young men is how certain terms - like “patriarchy” or “toxic masculinity” - act as instant shut-downs. These words while grounded in important social theory are often received not as invitations to reflect but as accusations. For young men who have struggled in their relationships, witnessed their fathers suffer in custody battles or been hurt themselves these terms can feel like a verdict that’s already been rendered.

As parents, educators and clinicians we need to meet young men where they are - not by diluting reality but by acknowledging the pain, confusion and frustration they feel without moralising it away. If the goal is to invite them into a healthier understanding of moral questions we must begin from a place of empathy and openness, not accusation.

Dialogue Over Debate

That same conversation with my son went back and forth, each of us trying to make sense of things trying to make sense of each other's points of view.

"Women can’t drive—"

"Love..."

"No, I don’t think I believe that. I’m saying, if I should say that, I'm sexist. But when people say men are trash, that’s... okay?"

I threw out some stats. He countered with severity. I said men drive more and further. He said men have more serious accidents. But in reality the subject is more complicated than a ‘this vs that’ (Cullen et al., 2021; De Winter & Dodou, 2010). We agreed in the end that generalisations are flawed. They erase nuance, they hurt and can lead to innumerable conflicts.

"So, who are the better drivers?" we both asked.

"Let’s just agree that generalisations are lazy."

He laughed. "Deal."

These moments aren’t about winning arguments. They’re about giving young people space to think out loud - to stumble, reflect, refine... and to grow.

The Silent Problem: Male Vulnerability

Male victims of intimate partner violence often go unsupported and the research confirms this (Hines & Douglas, 2010; Archer, 2000). Their experiences are mocked or dismissed. Institutions are built to protect women but often leave men invisible. Add to this the terror of false accusations. While statistically rare (Lisak et al., 2010), the idea of being wrongly accused carries enormous psychological weight and in a world where men are told to respect, to ask for consent, to be good - this fear can feel destabilising.

This isn’t about denying women’s suffering. It’s about recognising that pain doesn’t have a gender monopoly. And if we fail to acknowledge male vulnerability we leave young men susceptible to narratives that weaponise their hurt.

"Ok, well, women end relationships way more than men do and sometimes the way they do it is not right. We have emotions too…the exact same emotions. I mean, why sleep with us if you know you’re going to break it off?"

Unfairness is the name of the game here, regardless of the why behind it. The pain and rejection caused is not right… end of story. Empathy to try to understand ‘the other side’ is replaced by black-and-white thinking and looking for comfort or reinforced self-narratives that can open the door to outside influences on moral development.

The Vacuum: Enter the Influencers

A few years ago my eldest son sent me a video. "Ever heard of Andrew Tate?" At that stage I hadn’t.

I clicked, watched and my jaw dropped.

"Whhhhaaaattt?"

He laughed, knowingly. "He’s everywhere! And young boys like from the age of 12 are watching him." He was as incredulous as I was.

And there it was. A vacuum. Boys and young men searching for guidance, affirmation and clarity - and finding it in all the wrong places.

These influencers - from Andrew Tate to Jordan Peterson and everyone in between - don’t rise in isolation, they rise in silence and in the absence of real conversations, nuance and emotional safety. They offer a script for how to be a man, a justification for pain and a target for blame.

And they speak in a language boys recognise - confident, brash and unapologetic. And between the poles of Tate and Peterson lie countless quieter influences – memes, podcasters, YouTubers, Reddit threads - subtly reinforcing stereotypes under the guise of self-help, masculinity and “taking control of your life.” The entry point is often benign: fitness, focus, discipline - which in themselves are positive - but it can quickly morph into something else: adversarial worldviews and victim narratives.

So What Can We Do?

Create space for dialogue not debate. Validate their confusion without fuelling grievance and acknowledge this confusion in spaces where they can explore ideas without being shamed; model masculinity that is strong, ethical and open; teach complexity as strength not a threat and most importantly, let them question, reflect and revise.

We don’t need to coddle or lecture nor do we need to shout down when we feel offended and make them feel shame for thinking and learning to moralise at a post-conventional level. We do, however, need to stay close and remain the sounding board - even when what they say rattles us. Rather us than Andrew Tate.

From Dilemma to Dialogue

The fairness dilemma isn’t just a social tension. It’s a developmental turning point. The moment where a young man chooses:

Bitterness and Withdrawal? Or Growth?

And which path he takes depends on what’s available. Be that someone who listens without judging, because when your son says, "It’s not fair," what he’s really saying is:

Help me understand and belong, help me be good (though given where he’s at - the good vs bad debate is also on the table).

It doesn't mean he thinks hitting a woman is the right thing to do, even if first attacked by one.

As our conversation wound down I realised that I was seeing the world through my own lens - a woman who has known aggression and abuse at the hands of men, who has experienced true misogyny and unfair practices. But across from me sat a young man deeply convinced that his friends would never hurt a woman, no matter the statistics that are thrown at him.

But I’ve also seen women manipulate, belittle and emotionally harm their partners. Violence and abuse are not confined to one gender, even if they manifest differently.

Cole’s father - my husband - is one of the most masculine men I know. Tall, intense, seemingly emotionally reserved. But in over three decades together, he’s never once raised his hand against me nor has he raised his voice. His strength is not violent. It is quiet, confident and supportive. It casts a very long shadow - one that my sons are now learning to walk out from under, searching for their voices – and it’s not easy but they're finding it perhaps without even realising it yet.

Talk to and with your sons. Listen when they talk back. Because the conversations we have today shape the moral voices they carry forward.

References

Archer, J. (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 651–680. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651

Cullen, P., Moeller, H., Woodward, M., Senserrick, T., Boufous, S., Rogers, K., ... Ivers, R. (2021). Are there sex differences in crash and crash-related injury between male and female drivers? SSM – Population Health, 15, 100816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100816

De Winter, J. C. F., & Dodou, D. (2010). The Driver Behaviour Questionnaire as a predictor of accidents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Safety Research, 41(6), 463–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2010.10.007

Hines, D. A., & Douglas, E. M. (2010). Intimate terrorism by women towards men: Does it exist? Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 2(3), 36–56. https://doi.org/10.5042/jacpr.2010.0335

Kohlberg, L. (1984). Essays on Moral Development, Volume II: The Psychology of Moral Development. Harper & Row.

Lisak, D., Gardinier, L., Nicksa, S. C., & Cote, A. M. (2010). False allegations of sexual assault: An analysis of ten years of reported cases. Violence Against Women, 16(12), 1318–1334. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801210387747